Welcome to Napa County Historical Society

Dedicated to Napa County history since 1948

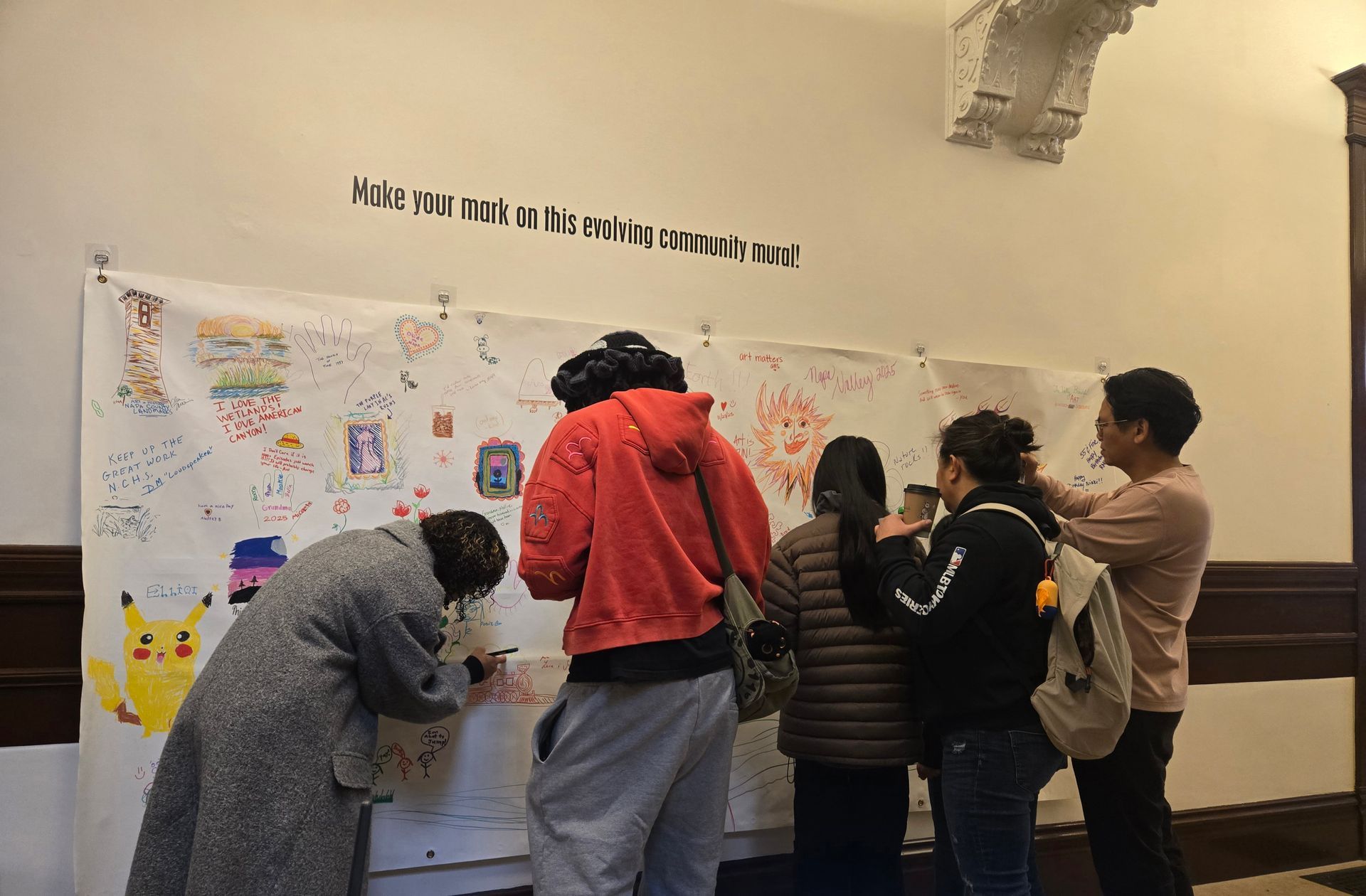

Since our founding, the Napa County Historical Society has served Napa County as the region’s leading source for historic exhibits, presentations, lectures, advocacy, and research. Today, we operate a museum and an active research library and archive in Downtown Napa’s historic Goodman Library, partnering with local organizations to preserve and share Napa County’s enduring heritage for all.

Our Impact

The Napa Historical Society is an amazing organization. It is a bridge between the past and present. We love that we get to be a part of maintaining the integrity of the history whether it is cataloguing archival documents or learning about the history through the exhibits. -ArcSolano

Contact Us

Thank you for contacting us.We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Oops, there was an error sending your message.Please try again later.